In a YA debut that’s Gossip Girl with a speculative twist, a Chinese American girl monetizes her strange new invisibility powers by discovering and selling her wealthy classmates’ most scandalous secrets.

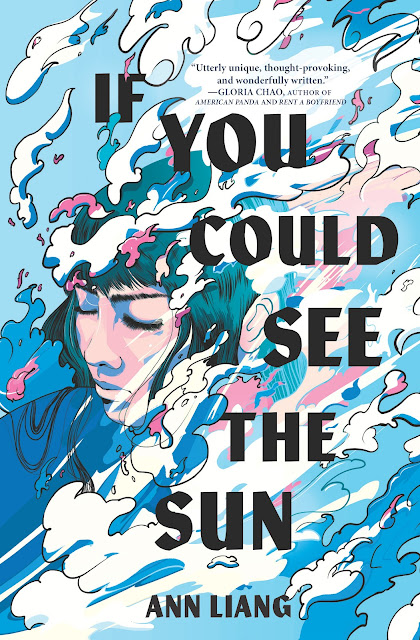

Title: If You Could See The Sun

Author: Ann Liang

Publisher: Inkyard Press

Genre: YA, Contemporary, Fantasy

Release Date: 11th October 2022

BLURB supplied by Harlequin Trade Publishing

Alice Sun has always felt invisible at her elite Beijing international boarding school, where she’s the only scholarship student among China’s most rich and influential teens. But then she starts uncontrollably turning invisible—actually invisible.

When her parents drop the news that they can no longer afford her tuition, even with the scholarship, Alice hatches a plan to monetize her strange new power—she’ll discover the scandalous secrets her classmates want to know, for a price.

But as the tasks escalate from petty scandals to actual crimes, Alice must decide if it’s worth losing her conscience—or even her life.

PURCHASE LINKS

Bookshop.org

IndieBound

B&N

Amazon

My parents only ever invite me out to eat for one of three reasons. One, someone’s dead (which, given the ninety-something members in our family WeChat group alone, happens more often than you’d think). Two, it’s someone’s birthday. Or three, they have a life-changing announcement to make.

Sometimes it’s a combination of all the above, like when my great-grandaunt passed away on the morning of my twelfth birthday, and my parents decided to inform me over a bowl of fried sauce noodles that they’d be sending me off to Airington International Boarding School.

But it’s August now, the sweltering summer heat palpable even in the air-conditioned confines of the restaurant, and no one in my immediate family has a birthday this month. Which, of course, leaves only two other possibilities…

The anxious knot in my stomach tightens. It’s all I can do not to run right back out through the glass double doors. Call me weak or whatever, but I’m in no state to handle bad news of any kind.

Especially not today.

“Alice, what you look so nervous for ya?” Mama asks as an unsmiling, qipao-clad waitress leads us over to our table in the back corner.

We squeeze past a crowded table of elderly people sharing a giant pink-tinted cream cake shaped like a peach, and what appears to be a company lunch, with men sweating in their stuffy collared shirts and women dabbing white powder onto their cheeks. A few of them twist around and stare when they notice my uniform. I can’t tell if it’s because they recognize the tiger crest emblazoned on my blazer pocket, or because of how grossly pretentious the design looks compared to the local schools’ tracksuits.

“I’m not nervous,” I say, taking the seat between her and Baba. “My face just always looks like this.” This isn’t exactly a lie. My aunt once joked that if I were ever found at a crime scene, I’d be the first one arrested based solely on my expression and body language. Never seen anyone as jumpy as you, she’d said. Must’ve been a mouse in your past life.

I resented the comparison then, but I can’t help feeling like a mouse now—one that’s about to walk straight into a trap.

Mama moves to pass me the laminated menu. As she does, light spills onto her bony hands from the nearby window, throwing the ropey white scar running down her palm into sharp relief. A pang of all-too-familiar guilt flares up inside me like an open flame.

“Haizi,” Mama calls me. “What do you want to eat?”

“Oh. Uh, anything’s fine,” I reply, quickly averting my gaze.

Baba breaks apart his disposable wooden chopsticks with a loud snap. “Kids these days don’t know how lucky they are,” he says, rubbing the chopsticks together to remove any splinters before helping me do the same. “All grow up in honey jar. You know what I eat at your age? Sweet potato. Every day, sweet potato.”

As he launches into a more detailed description of daily life in the rural villages of Henan, Mama waves the waitress over and lists off what sounds like enough dishes to feed the entire restaurant.

“Ma,” I protest, dragging the word out in Mandarin. “We don’t need—”

“Yes, you do,” she says firmly. “You always starve whenever school starts. Very bad for your body.”

Despite myself, I suppress the urge to roll my eyes. Less than ten minutes ago, she’d been commenting on how my cheeks had grown rounder over the summer holidays; only by her logic is it possible to be too chubby and dangerously undernourished at the same time.

When Mama finally finishes ordering, she and Baba exchange a look, then turn to me with expressions so solemn I blurt out the first thing that comes to mind: “Is—is my grandpa okay?”

Mama’s thin brows furrow, accentuating the stern features of her face. “Of course. Why you ask?”

“N-nothing. Never mind.” I allow myself a small sigh of relief, but my muscles remain tensed, as if bracing for a blow. “Look, whatever the bad news is, can we just—can we get it over with quickly? The awards ceremony is in an hour and if I’m going to have a mental breakdown, I need at least twenty minutes to recover before I get on stage.”

Baba blinks. “Awards ceremony? What ceremony?”

My concern temporarily gives way to exasperation. “The awards ceremony for the highest achievers in each year level.”

He continues to stare at me blankly.

“Come on, Ba. I’ve mentioned it at least fifty times this summer.”

I’m only exaggerating a little. Sad as it sounds, those fleeting moments of glory under the bright auditorium spotlight are all I’ve been looking forward to the past couple of months.

Even if I have to share them with Henry Li.

As always, the name fills my mouth with something sharp and bitter like poison. God, I hate him. I hate him and his flawless, porcelain skin and immaculate uniform and his composure, as untouchable and unfailing as his ever-growing list of achievements. I hate the way people look at him and see him, even if he’s completely silent, head down and working at his desk.

I’ve hated him ever since he sauntered into school four years ago, brand-new and practically glowing. By the end of his first day, he’d beat me in our history unit test by a whole two-point-five marks, and everyone knew his name.

Just thinking about it now makes my fingers itch.

Baba frowns. Looks to Mama for confirmation. “Are we meant to go to this—this ceremony thing?”

“It’s students only,” I remind him, even though it wasn’t always this way. The school decided to make it a more private event after my classmate’s very famous mother, Krystal Lam, showed up to the ceremony and accidentally brought the paparazzi in with her. There were photos of our auditorium floating around all over Weibo for days afterward.

“Anyway, that’s not the point. The point is that they’re handing out awards and—”

“Yes, yes, all you talk about is award,” Mama interrupts, impatient. “Where your priorities, hmm? Does that school of yours not teach you right values? It should go family first, then health, then saving for retirement, then—are you even listening?”

I’m spared from having to lie when our food arrives.

In the fancier Peking duck restaurants like Quanjude, the kind of restaurants my classmates go to frequently without someone having to die first, the chefs always wheel out the roast duck on a tray and carve it up beside your table. It’s almost an elaborate performance; the crispy, glazed skin coming apart with every flash of the blade to reveal the tender white meat and sizzling oil underneath.

But here the waitress simply presents us with a whole duck chopped into large chunks, the head still attached and everything.

Mama must catch the look on my face because she sighs and turns the duck head away from me, muttering something about my Western sensibilities.

More dishes come, one by one: fresh cucumbers drizzled with vinegar and mixed with chopped garlic, thin-layered scallion pancakes baked to a perfect crisp, soft tofu swimming in a golden-brown sauce and sticky rice cakes dusted with a fine coat of sugar. I can already see Mama measuring out the food with her shrewd brown eyes, most likely calculating how many extra meals she and Baba can make from the leftovers.

I force myself to wait until both Mama and Baba have taken few bites of their food to venture, “Um. I’m pretty sure you guys were going to tell me something important…?”

In response, Baba takes a long swig from his still-steaming cup of jasmine tea and swishes the liquid around in his mouth as if he’s got all the time in the world. Mama sometimes jokes that I take after Baba in every way—from his square jaw, straight brows and tan skin to his stubborn perfectionist streak. But I clearly haven’t inherited any of his patience.

“Baba,” I prompt, trying my best to keep my tone respectful.

He holds up a hand and drains the rest of his tea before at last opening his mouth to speak. “Ah. Yes. Well, your Mama and I were thinking… How you feel about going to different school?”

“Wait. What?” My voice comes out too loud and too shrill, cutting through the restaurant chatter and cracking at the end like some prepubescent boy’s. The company workers from the table nearby stop midtoast to shoot me disapproving looks. “What?” I repeat in a whisper this time, my cheeks heating.

“Maybe you go to local school like your cousins,” Mama says, placing a piece of perfectly wrapped Peking duck down on my plate with a smile. It’s a smile that makes alarm bells go off in my head. The kind of smile dentists give you right before yanking your teeth out. “Or we let you go back to America. You know my friend, Auntie Shen? The one with the nice son—the doctor?”

I nod slowly, as if two-thirds of her friends’ children aren’t either working or aspiring doctors.

“She says there’s very nice public school in Maine near her house. Maybe if you help work for her restaurant, she let you stay—”

“I don’t get it,” I interrupt, unable to help myself. There’s a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach, like that time I ran too hard in the school Sports Carnival just to beat Henry and nearly threw up all over the courtyard. “I just… What’s wrong with Airington?”

Baba looks a little taken aback by my response. “I thought you hated Airington,” he says, switching to Mandarin.

“I never said I hated—”

“You once printed out a picture of the school logo and spent an entire afternoon stabbing it with your pen.”

“So, I wasn’t the biggest fan in the beginning,” I say, setting my chopsticks down on the plastic tablecloth. My fingers tremble slightly. “But that was five years ago. People know who I am now. I have a reputation—a good one. And the teachers like me, like really like me, and most of my classmates think I’m smart and—and they actually care what I have to say…” But with every word that tumbles out of my mouth, my parents’ expressions grow grimmer, and the sick feeling sharpens into ice-cold dread. Still, I plow on, desperate. “And I have my scholarship, remember? The only one in the entire school. Wouldn’t it be a waste if I just left—”

“You have half scholarship,” Mama corrects.

“Well, that’s the most they’re willing to offer…” Then it hits me. It’s so obvious I’m stunned by own ignorance; why else would my parents all of a sudden suggest taking me out of the school they spent years working tirelessly to get me into?

“Is this… Is this about the school fees?” I ask, keeping my voice low so no one around us can overhear.

Mama says nothing at first, just fiddles with the loose button on her dull flower-patterned blouse. It’s another cheap supermarket purchase; her new favorite place to find clothes after Yaxiu Market was converted into a lifeless mall for overpriced knockoff brands.

“That’s not for you to worry,” she finally replies.

Which means yes.

I slump back in my seat, trying hard to collect my thoughts. It’s not as if I didn’t know that we’re struggling, that we’ve been struggling for some time now, ever since Baba’s old printing company shut down and Mama’s late shifts at Xiehe Hospital were cut short. But Mama and Baba have always been good at hiding the extent of it, waving away any of my concerns with a simple “just focus on your studies” or “silly child, does it look like we’d let you starve?”

I look across the table at them now, really look at them, and what I see is the scattering of white hairs near Baba’s temples, the tired creases starting to show under Mama’s eyes, the long days of labor taking their toll while I stay sheltered in my little Airington bubble. Shame roils in my gut. How much easier would their lives be if they didn’t have to pay that extra 165,000 RMB every year?

“What, um, were the choices again?” I hear myself say. “Local Beijing school or public school in Maine?”

Evident relief washes over Mama’s face. She dips another piece of Peking duck in a platter of thick black sauce, wraps it tight in a sheet of paper-thin pancake with two slices of cucumber—no onions, just the way I like it—and lays it down on my plate. “Yes, yes. Either is good.”

I gnaw on my lower lip. Actually, neither option is good.

Going to any local school in China means I’ll have to take the gaokao, which is meant to be one of the hardest college entrance exams as it is without my primary school–level Chinese skills getting in the way. And as for Maine—all I know is that it’s the least diverse state in America, my understanding of the SATs is pretty much limited to the high school dramas I’ve watched on Netflix, and the chances of a public school there letting me continue my IB coursework are very low.

“We don’t have to decide right now,” Mama adds quickly. “Your Baba and I already pay for your first semester at Airington. You can ask teachers, your friends, think about it a bit, and then we discuss again. Okay?”

“Yeah,” I say, even though I feel anything but okay. “Sounds great.”

Baba taps his knuckles on the table, making both of us start. “Aiya, too much talking during eating time.” He jabs his chopsticks at the plates between us. “The dishes already going cold.”

As I pick up my own chopsticks again, the elderly people at the table beside us start singing the Chinese version of “Happy Birthday,” loud and off-key. “Zhuni shengri kuaile… Zhuni shengri kuaile…” The old nainai sitting in the middle nods and claps her hands together to the beat, smiling a wide, toothless grin.

At least someone’s leaving this restaurant in higher spirits than when they came in.

Sweat beads and trickles from my brow almost the instant I step outside. The kids back in California always complained about the heat, but the summers in Beijing are stifling, merciless, with the dappled shade of wutong trees planted up and down the streets often serving as the sole source of relief.

Right now it’s so hot I can barely breathe. Or maybe that’s just the panic kicking in.

“Haizi, we’re going,” Mama calls to me. Little plastic take-out bags swing from her elbow, stuffed full with everything—and I mean everything—left over from today’s lunch. She’s even packed the duck bones.

I wave at her. Exhale. Manage to nod and smile as Mama lingers to offer me her usual parting words of advice: Don’t sleep later than eleven or you die, don’t drink cold water or you die, watch out for child molesters on your way to school, eat ginger, lot of ginger, remember check air quality index every day…

Then she and Baba are off to the nearest subway station, her petite figure and Baba’s tall, angular frame quickly swallowed up by the crowds, and I’m left standing all alone.

A terrible pressure starts to build at the back of my throat.

No. I can’t cry. Not here, not now. Not when I still have an awards ceremony to attend—maybe the last awards ceremony I’ll ever go to.

I force myself to move, to focus on my surroundings, anything to pull my thoughts from the black hole of worry swirling inside my head.

An array of skyscrapers rises up in the distance, all glass and steel and unabashed luxury, their tapered tips scraping the watery-blue sky. If I squint, I can even make out the famous silhouette of the CCTV headquarters. Everyone calls it The Giant Underpants because of its shape, though Mina Huang— whose dad is apparently the one who designed it—has been trying and failing for the past five years to make people stop.

My phone buzzes in my skirt pocket, and I know without looking that it’s not a text (it never is) but an alarm: only twenty minutes left until assembly begins. I make myself walk faster, past the winding alleys clogged with rickshaws and vendors and little yellow bikes, the clusters of convenience stores and noodle shops and calligraphed Chinese characters blinking across neon signs all blurring by.

The traffic and crowds thicken as I get closer toward the Third Ring Road. There are all kinds of people everywhere: balding uncles cooling themselves with straw fans, cigarettes dangling out of mouths, shirts yanked halfway up to expose their sunburned bellies, the perfect picture of I-don’t-give-a-shit; old aunties strutting down the sidewalks with purpose, dragging their floral shopping trolleys behind them as they head for the open markets; a group of local school students sharing large cups of bubble tea and roasted sweet potatoes outside a mini snack stall, stacks of homework booklets spread out on a stool between them, gridded pages fluttering in the breeze.

As I stride past, I hear one of the students ask in a dramatic whisper, their words swollen with a thick Beijing accent, “Dude, did you see that?”

“See what?” a girl replies.

I keep walking, face forward, doing my best to act like I can’t hear what they’re saying. Then again, they probably assume I don’t understand Chinese anyway; I’ve been told time and time again by locals that I have a foreigner’s air, or qizhi, whatever the hell that’s supposed to mean.

“She goes to that school. That’s where that Hong Kong singer—what’s her name again? Krystal Lam?—sends her daughter, and the CEO of SYS as well… Wait, let me just Baidu it to check…”

“Wokao!” the girl swears a few seconds later. I can practically feel her gaping at the back of my head. My face burns. “330,000 RMB for just one year? What are they teaching, how to seduce royalty?” Then she pauses. “But isn’t it an international school? I thought those were only for white people.”

“What do you know?” the first student scoffs. “Most international students just have foreign passports. It’s easy if you’re rich enough to be born overseas.”

This isn’t true at all: I was born right here in Beijing and didn’t move to California with my parents until I was seven. And as for being rich… No. Whatever. It’s not like I’m going to turn back and correct him. Besides, I’ve had to recount my entire life story to strangers enough times to know that sometimes it’s easier to just let them assume what they want.

Without waiting for the traffic lights to turn—no one here really follows them anyway—I cross the road, glad to put some distance between me and the rest of their conversation. Then I make a quick to-do list in my head.

It’s what works best whenever I’m overwhelmed or frustrated. Short-term goals. Small hurdles. Things within my control. Like:

One, make it through entire awards ceremony without pushing Henry Li off the stage.

Two, turn in Chinese essay early (last chance to get in Wei Laoshi’s good graces).

Three, read history course syllabus before lunch.

Four, research Maine and closest public schools in Beijing and figure out which place offers highest probability of future success—if any—without breaking down and/or hitting something.

See? All completely doable.

Excerpted from If You Could See the Sun by Ann Liang, Copyright © 2022 by Ann Liang. Published by Inkyard Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ann Liang is an undergraduate at the University of Melbourne. Born in Beijing, she grew up travelling back and forth between China and Australia, but somehow ended up with an American accent. When she isn’t stressing out over her college assignments or writing, she can be found making over-ambitious to-do lists, binge-watching dramas, and having profound conversations with her pet labradoodle about who’s a good dog. This is her debut novel.

Author website: https://www.annliang.com/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/annliangwrites/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/annliangy

No comments:

Post a Comment